Comic Book History Lesson: Censorship And The Comics Code Authority

One of the most annoying things you can say to a comic book collector is that comic books are for kids and not adults.

It’s a chilling insult that implies the comics they read never advanced beyond their funny-page beginnings. However, it is also a blunt reminder of one of the most disruptive things to ever happen to the comic book industry.

Approximately 65 years ago, during the era of McCarthyism, comic books became a threat, causing a panic that culminated in a Senate hearing in 1954. This, of course, isn’t to say that McCarthyism and the comic book panic were comparable in their human toll, but they share the same symptoms of American fear and a extreme, reactive response to it.

The reaction to the supposed dangers of comic books was the Comics Code — a set of rules that spelled out what comics could and couldn’t do. To name a few: Good had to triumph over evil. Government had to be respected. Marriages never ended in divorce. And it was in publishers’ best interests to remain compliant with the code.

What ignorant adults in politics thought was best for children ended up censoring and dissolving years of progress and artistry, as well as comics that challenged American views on gender and race. Consequently, that cemented the idea that this was a medium for kids — something we’ve only recently started to dispel thanks to the movie industry’s successfully adapted comic book movies and widely popular comic cons. For awesome stories, consider checking out the comic books we have in our online comic book store.

The Peak of Comic Books

As many know, comic books began as collections of newspaper comic strips. Newspaper publishers wanted to eke out every last drop of profit they could, and comics were a way to keep presses running on weekends. These collections began in the 1930s, and eventually publishers saw the potential profits in original content. In 1938, Action Comics No. 1, the issue that brought Superman and superheroes into our lives, marked the turn of the comics industry.

1938 to 1950 was a period historians refer to as comics’ Golden Age — comic books flourished without any direct competition. Stories of men lifting up cars — complete with engaging art were more fun than costly hardcover books, ideal for an audience during the Great Depression and World War II offering entertainment that the radio couldn’t.

Everyone was reading them, and the people producing comic books at the time — illustrators, writers, creators — were often immigrants and minorities who were shut out of more respected fields of publishing in one way or another.

“Comic books, even more so than newspaper strips before them, attracted a high quotient of creative people who thought of more established modes of publishing as foreclosed to them,” author David Hajdu wrote in his book The Ten-Cent Plague. “[I]mmigrants and children of immigrants, women, Jews, Italians, Negroes, Latinos, Asians, and myriad social outcasts, as well as some like [Will] Eisner who, in their growing regard for comic books as a form, became members of a new minority.”

Characters developed during this period are still among the most popular today. Wonder Woman, Batman, Superman, the Human Torch, and Captain America were all created during the Golden Age.

These titles also explored social issues and put women equal to men when it came to crime fighting.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2514058/Screen_Shot_2014-12-03_at_11.22.08_AM.0.png)

There was also Lady Satan. Ms. Satan and her fiancé were attacked by Nazis while on a boat. Her fiancé died after the boat sank, and Satan then pledged to defeat Nazis at every opportunity:

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2536470/lady-satan-1.0.png)

And there was a book called All-Negro Comics, published in 1947, which was made by black writers and drawn by black artists, and featured black characters in children’s features and crime mysteries:

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2514068/0.0.jpg)

It seemed as if everyone was writing comics. And everyone was consuming comic books. In 1948, the 80 million to 100 million comic books purchased in America every month generated annual revenue for the industry of at least $72 million. And remember that comic books were sold for just nickels and dimes.

An Industry Doesn’t Just Go Bad Overnight

More and more comics began to spread their wings and explore cultural passions and interests. Some of these dipped into gore and horror. EC Comics, run by William Gaines, was one of these great companies. It began publishing horror comics like Tales from The Crypt; Grim Fairy Tale, which re-imagined classic fairy tales in gruesome fashion and tell violent graphic crime stories.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2514108/ECComics.0.jpg)

Consequently, a large percentage of adults wanted to crack down on that art, primarily the violence, horror, and gore for which EC was becoming known for among readers. This voices of opposition mostly came from church and family groups trying to tie comics to juvenile delinquency despite the facts saying otherwise.

This isn’t unlike the way people like to tie video games to violent crime in current times. In both cases, instead of looking to outliers who consume particular forms of media as just that, those outliers become an unfounded generalization applied to the consumers as a whole, ignoring the millions who read comics or play video games and don’t become violent or criminals.

The man in charge of tying comic books to society’s ills was a German-American psychiatrist and author named Fredric Wertham.

Wertham was employed at Harlem hospital treating juvenile delinquents when he observed that those he treated read comic books. At the time everyone was reading comic books, so the fact that the delinquents were doing so was not particularly noteworthy — except to Wertham of course.

Comics became his “holy crusade”. According to the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, Wertham’s public attacks on comic books started in a 1948 interview with Collier’s Magazine called “Horror in the Nursery.” From there, Wertham spoke at a symposium called “The Psychopathy of Comic Books,” explaining his belief that comic book readers were sexually aggressive and that this led to them committing crimes.

Going back over his research now, it appears Wertham fudged and disingenuously represented what he had found. But at the time, people trusted him. They followed his lead, resulting in events like a public comic book burning by a Girl Scout troop from Cape Girardeau, Missouri.

Wertham’s crowning achievement against comic books came in 1954 when he published his book The Seduction of the Innocent. Turns out that his book featured bad research. It made hard-to-substantiate claims, suggesting Wonder Woman was a lesbian, Batman and Robin were gay, and comic books were leading children into danger. And it did not help that Wertham’s comic book witch-hunt coincided with McCarthyism in the US, adding fuel to the fire.

Wertham’s work caught the eye of Carey Estes Kefauver, a Democratic senator from Tennessee. Kefauver eventually chaired a Senate subcommittee that gave an even larger platform to Wertham’s panicked arguments against comic books.

But Kefauver had a different agenda. He was tough on crime, and comic book distributors had ties with the mob.

“His reputation was a mob hunter,” Miller told me. “It happened that comic book distribution, like most other magazine distribution at the time, was either run by organized crime or had strong elements of organized crime in it.”

Kefauver’s Senate hearing was televised and shifted the public perception on comic books. It made the New York Times front page. And Wertham said comic books scared him more than Hitler:

Well, I hate to say that, Senator, but I think Hitler was a beginner compared to the comic-book industry. They get the children much younger. They teach them race hatred at the age of 4 before they can read.

Censorship wasn’t the only battle the comic book industry was fighting.

“Something else going on demographically — comics were losing the race against television,” Miller explains.

Television began to hits its stride and became comics’ natural enemy, competing for readers’ time and attention. That was a punch the industry took to the jaw. But Wertham was the boot to the neck.

The Comics Code

The government never acted beyond the hearing. Kefauver dropped interest in comic books because he had bigger political dreams to pursue — he was selected as presidential candidate Adlai Stevenson‘s running mate in 1956.

That didn’t stop the comics industry from feeling the hearing’s effects. Sean Howe, author of Marvel Comics: The Untold Story, points out that 15 publishers went out of business the summer after the April hearings. The only surviving publication from EC Comics was Mad magazine.

In order to save face, the surviving comic book publishers, acting as the Association of Comics Magazine Publishers, cobbled together an organization called the Comics Code Authority and a code that would appease the Wertham-stoked flames. It included:

- A crackdown on “sexy” images; no nude images

- Criminals should always be bad and never triumph over good. Comics should make it clear that they should not be imitated.

- Authority figures (cops, government officials, organizations) should be respected.

- A ban on torture.

- Werewolves, zombies, vampires, and ghouls couldn’t be used.

- Entreaties against slang and “vulgar” language.

- An order to respect the sanctity of the family (i.e., no divorce or gay people).

- A ban on comics dealing in racial and religious prejudice — this sounds good in theory, but as the Comic Book Defense League Fund points out, it eliminated stories that challenged the religious beliefs of Comic Code administrator Charles F. Murphy and reduced representation of nonwhite people.

If a comic passed these tests, it would receive a seal of approval. And distributors only wanted to carry comics with the Comics Code seal.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2536506/cca-seal.0.jpg)

The seal of approval.

Comics were neutered.

The beauty of pre-code comics was that they told myriad of different stories featuring different people, like those women who were lowering the boom on Nazis or black detective Ace Harlem in All-Negro Comics. The worlds characters lived in were fictional, but they showed us hope and horror. They gave shape to promising concepts and form to dastardly darkness.

The code got rid of all of that beauty and pressed each book, each writer, and each creator into a painful mold of conformity.

“All of the other genres that aren’t superheroes — they all tend to fall away in the years following the code,” Miller said. “By the ’60s, you saw the end of romance books and Western comics. Kids’ publishers will be gone by 1964.”

The code is the reason superheroes became popular with creators and artists again. It was fairly easy to graft the tenets of the Comics Code onto a story of a do-gooder. Superheroes were a safe bet and allowed surviving publishers to rally around the biggest demographic said heroes appealed to: teenage boys.

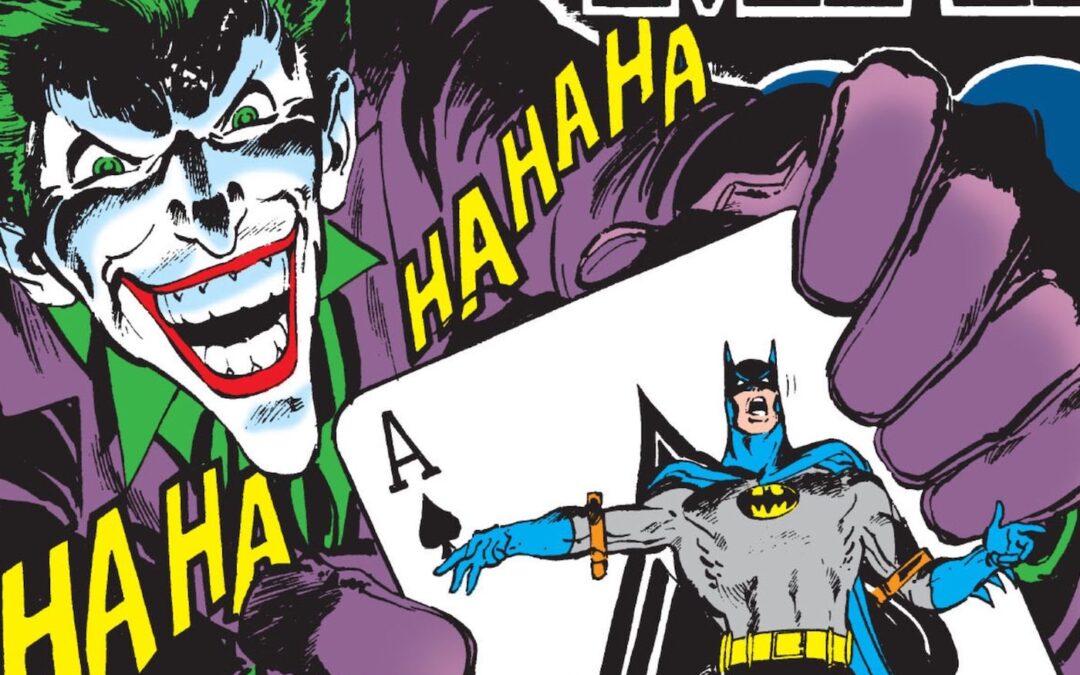

But even superheroes got repetitive. Comic scripts at the time usually consisted of a goofy villain launching some dastardly (but not too dastardly) plot before eventually getting caught by a superhero.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2536432/Screen_Shot_2014-11-08_at_6.33.25_PM.0.0.png)

“Superheroes, by their nature, tend to limit the stories you can tell, probably just as much as whether you can show nudity,” Howe said. “It’s unimaginable in other forms of entertainment, like books or movies, that you would just have romance novels or detective movies and no other kinds of movies or novels.”

By bending to the will of the code, comics started to feel redundant — like different singers covering the same song over and over. It isn’t hard to see why comics began losing the audience that had ravenously consumed 80 to 100 million issues per month just six years earlier. And television didn’t have to work very hard to grab this uninterested audience.

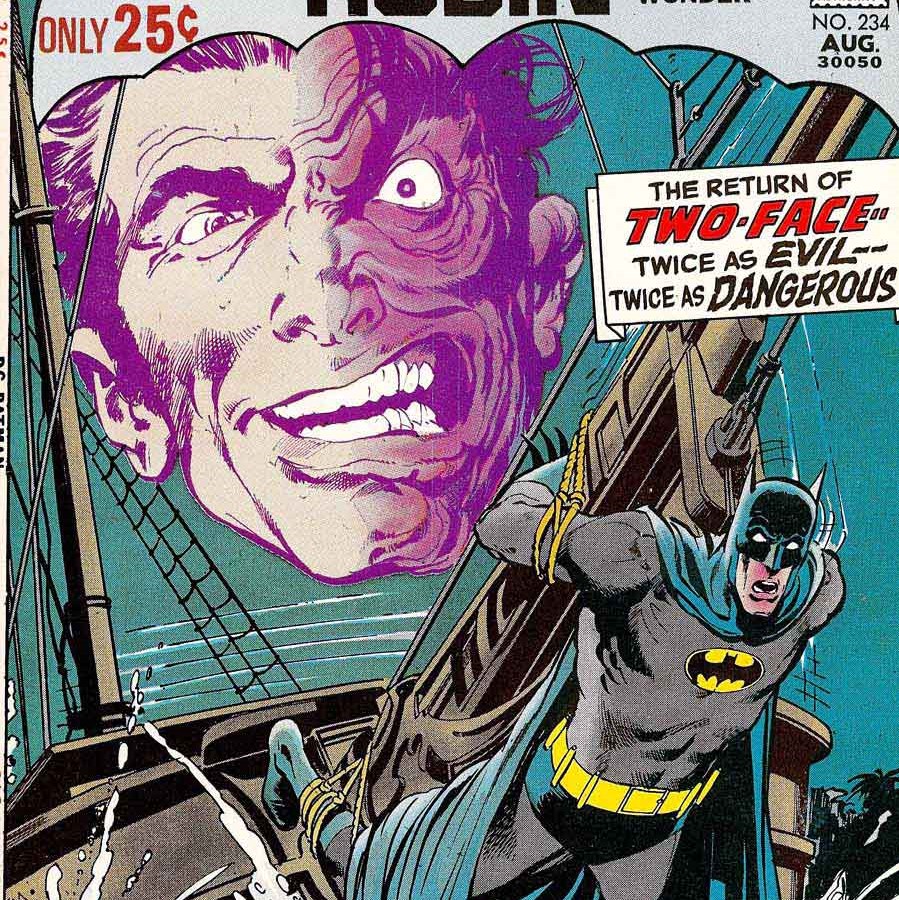

One of the clearest examples of the code’s effect is in the evolution of Batman. Batman, as we know him today, was a hero created by one of the darkest episodes in comics — he witnessed a mugger shoot and kill both his parents when he was a child. In 1939, he was painted as a character that was dark, ominous, and used guns.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2528640/detectivecomics.0.jpg)

During the comics backlash and throughout Wertham’s press tour, Batman was targeted for all of those things (his gun use was dealt with before the Comics Code), and Wertham also insisted that Batman and Robin were homosexual. In response, Batman was written to be friendlier, brighter, and more heterosexual. Batman’s love interest Vicki Vale was introduced in 1949 (a year after Wertham first burst onto the scene).

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2528682/Screen_Shot_2014-12-08_at_12.49.12_AM.0.png)

And characters like the kid-friendly Bat-Mite popped up:

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2528680/Bat_Mite_Cover.0.jpg)

The softening of Batman made him less interesting and less serious. This would also show up in the Adam West-led television series in 1966. Though we can now recognize the subversiveness and camp of the show, at the time, it was still a reflection of the lack of edge in the source material.

“When you start making everything acceptable for children, you tend to be just appealing to children or adolescents,” Howe said.

An appreciation for the artists who elevated their art

With this code in place, underground comics emerged and gained popularity. They didn’t have to abide by the code and offered saucier material than what mainstream comics were producing.

“If you were to talk to mainstream comic writers of a certain generation, they probably didn’t even think twice about what they were allowed to do,” Howe told me. “It had just been ingrained in them.”

But even in the mainstream, there were creators who took the form to a new level by challenging and circumventing the code. Marvel’s Roy Thomas gave readers the dark and twisted Ultron in 1968, a Trojan horse brimming with an Oedipus complex and a macabre message about technology and control. Thomas coyly lampooned the type of villains that peppered comic books in the wake of the Comics Code by making them Ultron’s henchmen.

There was also the legendary Jack Kirby, who hid commentary on huge political and social ideas within the superhero genre. Further, Howe points out that the cosmic comics of the ’70s delicately danced around the idea of psychedelic drugs.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2525734/asm-97-2.0.jpg)

Stan Lee had what’s considered the biggest “F you” to the code in 1971, when he crafted a drug abuse storyline in Amazing Spider-Man Nos. 96 through 98. That move chipped away at the power of the code. DC Comics followed Lee’s example that year with a drug abuse story of its own, in Green Lantern/Green Arrow Nos. 85 and 86.

In the years following Lee’s revolt, the code was rewritten and ratified. Its loosening grip allowed creators to explore darker topics and make villains who were just as interesting as the heroes. (Remember: one of the code’s rules was that readers couldn’t sympathize with a villain.) That’s the difference between someone like Spider-Man’s sort of silly Shocker and X-Men’s charismatic Magneto.

The final nail in the code’s coffin wasn’t something artists or creators did. It’s a lot more boring and has to do with the direct market. Comic book shops began popping up in the ’70s. As time went on, publishers weren’t indebted to their distributors, and a new distribution method allowed them to sell stories to shops that didn’t have the code’s seal of approval.

“Comics started being distributed this way and didn’t have to have the Comics Code,” Miller told me. “And at that point, people began realizing that they want to write comics that were challenging and interesting. Over the years, one publisher after the other started dropping the code.”

Today, with the rise of digital comics, the audiences that read comics in the first half of the 20th century are finally coming back. Digital comics, for instance, appear to appeal to female readers. And the creativity has returned. Stunningly good books like Bitch Planet and The Wicked + The Divine — books that would have been banned by the code — came out this year, and they’re just the latest in the long, ever-growing lines of comics that push the boundaries of the art form.

But it’s not hard to wonder: What would have happened to superheroes if the code never existed? Could this renaissance have happened sooner? And what kinds of stories did we miss out on, thanks to generations of creativity stunted by the Comics Code?